ATLANTA, Ga. – In an opinion published Monday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld a district court’s injunction barring enforcement of most provisions of a Florida law which, among other things, prohibits large social media companies from “deplatforming” political candidates for any reason, prioritizing (or deprioritizing) any post “by or about” a political candidate and removing anything posted on their platforms by a “journalistic enterprise” based on the content of that post.

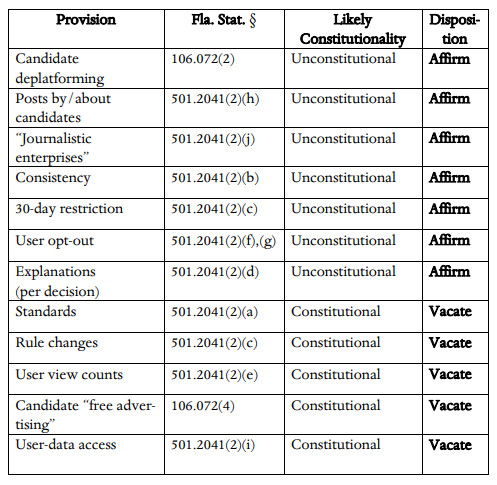

In its 67-page opinion, the appellate panel strongly rejected nearly every argument Florida made in support of the law, except provisions pertaining to the law’s user-data access requirements. (See the chart at the bottom of this post for a breakdown of which portions of the law the court finds constitutional and unconstitutional.)

In defending the law, one of Florida’s primary arguments has been that the law doesn’t trigger scrutiny under the First Amendment at all, asserting that social media companies don’t engage in “speech” themselves – a line of reasoning the court flatly rejected as inconsistent with both precedent and logic.

As noted by the court, Florida maintains that “because the vast majority of content that makes it onto social-media platforms is never reviewed—let alone removed or deprioritized— platforms aren’t engaged in conduct of sufficiently expressive quality to merit First Amendment protection.”

“With respect, the State’s argument misses the point,” the court wrote in its opinion. “The ‘conduct’ that the challenged provisions regulate—what this entire appeal is about—is the platforms’ ‘censorship’ of users’ posts—i.e., the posts that platforms do review and remove or deprioritize. The question, then, is whether that conduct is expressive. For reasons we’ve explained, we think it unquestionably is.”

Citing the most squarely on-point case law, the court held that taken together, “Miami Herald, Pacific Gas, and particularly Turner and Hurley establish that a private entity’s decisions about whether, to what extent, and in what manner to disseminate third party-created content to the public are editorial judgments protected by the First Amendment.”

“Whether we assess social-media platforms’ content-moderation activities against the Miami Herald line of cases or against our own decisions explaining what constitutes expressive conduct, the result is the same: Social-media platforms exercise editorial judgment that is inherently expressive,” the court added. “When platforms choose to remove users or posts, deprioritize content in viewers’ feeds or search results, or sanction breaches of their community standards, they engage in First-Amendment-protected activity.”

What’s more, the court observed, the Florida legislature’s stated rationale for passing the law in the first place favors a finding that social media platforms engage in First Amendment-protected expression.

“(T)he driving force behind S.B. 7072 seems to have been a perception (right or wrong) that some platforms’ content-moderation decisions reflected a ‘leftist’ bias against ‘conservative’ views—which, for better or worse, surely counts as expressing a message,” the court wrote. “That observers perceive bias in platforms’ content-moderation decisions is compelling evidence that those decisions are indeed expressive.”

The court also observed a hint of irony implicit in the law: In crafting a response to what the legislature sees as a liberal bias in the world of Big Tech, Florida created a law which would infringe on the First Amendment rights of platforms that lean to the right, as well.

“Because a social-media platform itself ‘spe[aks]’ by curating and delivering compilations of others’ speech—speech that may include messages ranging from Facebook’s promotion of authenticity, safety, privacy, and dignity to ProAmericaOnly’s ‘No BS | No LIBERALS’—a law that requires the platform to disseminate speech with which it disagrees interferes with its own message and thereby implicates its First Amendment rights,” the court wrote.

The appellate panel also wasn’t persuaded by Florida’s argument that social media platforms are, or should be considered, “common carriers.” For that matter, the court seemed a little unclear on what the state’s common carrier argument was, exactly.

“At the outset, we confess some uncertainty whether the State means to argue (a) that platforms are already common carriers, and so possess no (or only minimal) First Amendment rights, or (b) that the State can, by dint of ordinary legislation, make them common carriers, thereby abrogating any First Amendment rights that they currently possess,” the court wrote. “Whatever the State’s position, we are unpersuaded.”

For starters, the court observed, social media companies “have never acted like common carriers.”

“While it’s true that social-media platforms generally hold themselves open to all members of the public, they require users, as preconditions of access, to accept their terms of service and abide by their community standards,” the court observed. “In other words, Facebook is open to every individual if, but only if, she agrees not to transmit content that violates the company’s rules. Social-media users, accordingly, are not freely able to transmit messages ‘of their own design and choosing’ because platforms make—and have always made—‘individualized’ content- and viewpoint-based decisions about whether to publish particular messages or users.”

The court also noted that “Supreme Court precedent strongly suggests that internet companies like social-media platforms aren’t common carriers.”

“While the Court has applied less stringent First Amendment scrutiny to television and radio broadcasters, the Turner Court cabined that approach to ‘broadcast’ media because of its ‘unique physical limitations’—chiefly, the scarcity of broadcast frequencies,” the appellate panel wrote. “Instead of ‘comparing cable operators to electricity providers, trucking companies, and railroads—all entities subject to traditional economic regulation’—the Turner Court ‘analogized the cable operators [in that case] to the publishers, pamphleteers, and bookstore owners traditionally protected by the First Amendment.’ And indeed, the Court explicitly distinguished online from broadcast media in Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, emphasizing that the ‘vast democratic forums of the Internet’ have never been ‘subject to the type of government supervision and regulation that has attended the broadcast industry.’

“These precedents demonstrate that social-media platforms should be treated more like cable operators, which retain their First Amendment right to exercise editorial discretion, than traditional common carriers,” the appellate court concluded.

The court then noted that if “social-media platforms are not common carriers either in fact or by law, the State is left to argue that it can force them to become common carriers, abrogating or diminishing the First Amendment rights that they currently possess and exercise.”

“Neither law nor logic recognizes government authority to strip an entity of its First Amendment rights merely by labeling it a common carrier,” the court wrote. “Quite the contrary, if social-media platforms currently possess the First Amendment right to exercise editorial judgment, as we hold it is substantially likely they do, then any law infringing that right—even one bearing the terminology of ‘common carri[age]’—should be assessed under the same standards that apply to other laws burdening First-Amendment-protected activity.”

The court identified Florida’s “best rejoinder” to these points as being the state’s argument that “because large social-media platforms are clothed with a ‘public trust’ and have ‘substantial market power,’ they are (or should be treated like) common carriers.”

“These premises aren’t uncontroversial, but even if they’re true, they wouldn’t change our conclusion,” the court wrote. “The State doesn’t argue that market power and public importance are alone sufficient reasons to recharacterize a private company as a common carrier; rather, it acknowledges that the ‘basic characteristic of common carriage is the requirement to hold oneself out to serve the public indiscriminately.’”

“The problem, as we’ve explained, is that social-media platforms don’t serve the public indiscriminately but, rather, exercise editorial judgment to curate the content that they display and disseminate,” the court continued. “But the Supreme Court has squarely rejected the suggestion that a private company engaging in speech within the meaning of the First Amendment loses its constitutional rights just because it succeeds in the marketplace and hits it big.”

“In short, because social-media platforms exercise—and have historically exercised—inherently expressive editorial judgment, they aren’t common carriers, and a state law can’t force them to act as such unless it survives First Amendment scrutiny,” the court wrote.

In an amusing aside, the court also observed that certain provisions of the Florida law, taken in combination, could lead to outcomes its hard to imagine the state – or many of its conservative residents – would favor.

The court noted that sections of the§§ 106.072(2) and 501.2041(2)(h) of the Florida law “prohibit deplatforming, deprioritizing, or shadow-banning candidates regardless of how blatantly or regularly they violate a platform’s community standards and regardless of what alternative avenues the candidate has for communicating with the public.”

“These provisions would apply, for instance, even if a candidate repeatedly posted obscenity, hate speech, and terrorist propaganda,” the court observed. “The journalistic-enterprises provision requires platforms to allow any entity with enough content and a sufficient number of users to post anything it wants—other than true “obscen[ity]”— and even prohibits platforms from adding disclaimers or warnings…. As one amicus vividly described the problem, the provision is so broad that it would prohibit a child friendly platform like YouTube Kids from removing—or even adding an age gate to—soft-core pornography posted by PornHub, which qualifies as a ‘journalistic enterprise’ because it posts more than 100 hours of video and has more than 100 million viewers per year.”

The upshot of the 11th Circuit’s opinion is that the injunction granted by the district court is affirmed in part, vacated in part and the case is now remanded to the district court for trial. The chart below shows which portions of the law remain enjoined as likely unconstitutional and which the appellate panel believes could survive scrutiny.